Interview with interdisciplinary artist Courtney Kessel

Originally published in February 2017 on FEM-MEDIA-ART, a project by artist Colleen Keough

By Daniel J King

Punctuated by frequent coffee refills in the warm glow of the midday crowd at a favorite hideout, on a cold day in Athens, Ohio, artist Courtney Kessel and I discussed the development of her work, the space of the domestic, and how performance fits into the parent-child relationship.

Kessel works in performance, sculpture, installation, video and photography. Her projects re-contextualize materal from her domestic life in conceptually poetic ways. One thing I’m really taken with in her practice, is the extent to which her processes co-mingle the materials, actions, and labor of the mother and the artist. The inclusion of her daughter Chloé in the conception and making of some of her work is the most obvious example of this.

Putting the mother in the gallery is partially out of protest, describes Kessel. Her representation of the mother is intended as a real, subjective, elated, grumpy, sexy, frustrated, proud mother who wishes to express herself in that space. The mother arrives in the gallery with a voice.

DK: Does your artistic practice provide you some reflective distance from your daily life, a means of savoring it, digesting it, or understanding it?

CK: In terms of the practice being a way to think about parenting, a way to step back, that’s an interesting question. I often think about applying my domestic role and my role as a parent into my artist practice, but I don’t often think about it as a reflective practice to think about my home life. Now, having worked in the realm of the maternal for eight years, I start to think about what it means to involve Chloé in this process, especially since she’s getting older now.

Parenting is a constantly shifting thing, the child grows, we are getting older, and our relationship changes. My practice and my dedication to the maternal changes with that shift. In order to stay in balance, we have to shift again. Her role in my work shifts sublty as we grow and change. My child’s active participation also changes in the domestic space, which then must be considered in the artistic practice. As she gets older she takes on more responsibility at home, and perhaps she’ll take on more active roles in my practice. In Balance With, You and Me Tango piece, Sharing Space, and Spaces In Between are dependent on my direct relationship with Chloé. Whereas other pieces are less direct.

DK: Are you conscious of performance in everyday life, like when you’re home with your daughter, on a daily basis? For instance, have you thought about how performing happens in the domestic space? Altering behaviour to be a better example, for instance?

CK: That’s interesting to think about, this idea of the adult performing for the child. The performative aspects of daily life, I guess this is like putting your best foot forward in daily life, where people who don’t have kids may not have to think about it. Parenting is not for the faint of heart, you can’t just do what you want to do, without thinking about this other person.

DK: Talk about how the concepts of maternal subjectivity and performing motherhood relate?

CK: Both converge under the concept of visibility, so both are directed toward making the maternal more visible, within the space of the gallery and publicly, as opposed to being assumed, a projection of an ideal – like the iconographic madonna. Instead I’m attempting to give voice to the subjective maternal, the felt experience, which answers a frequent question concerning Chloé’s participation. It’s not all about her. It’s because of her.

Subjectivity is in the reality of the day to day experience. Performing motherhood is found in the visibility, putting it into the public space, making it the subject of the work. And perhaps it also relates to performing for my child as well, which is interesting because that happens in public and private spaces. Hiding the things you don’t want them to see, or even intentionally showing the things you do want them to see.

DK. How is your practice shifting? You’ve said you feel like you now have a gallery practice, rather than a studio practice. Can you talk a little about that?

CK: Not having a studio is how it all shifted. Parenting, not having enough space, and time influences my practice. Even now, Chloé is 12, but it’s still hard to go away to a studio. After school there are so few hours before bedtime, and you have to fit dinner in somewhere, and homework sometimes—being a parent there’s such a minute amount of time! So I guess that is part of the shift toward a gallery practice, which is very heavy in conceptualization and thinking about how an exhibit fits into my body of work, my interests and research. I’m always thinking about what steps forward will continue my interest in the feminist maternal, in different voices. The gallery practice is still a performance, it’s still being presented to an audience. That immediate feedback loop you get in performance, you also get in academia—in the classroom, in critiques, with your peer group, which you don’t have once you leave academia.

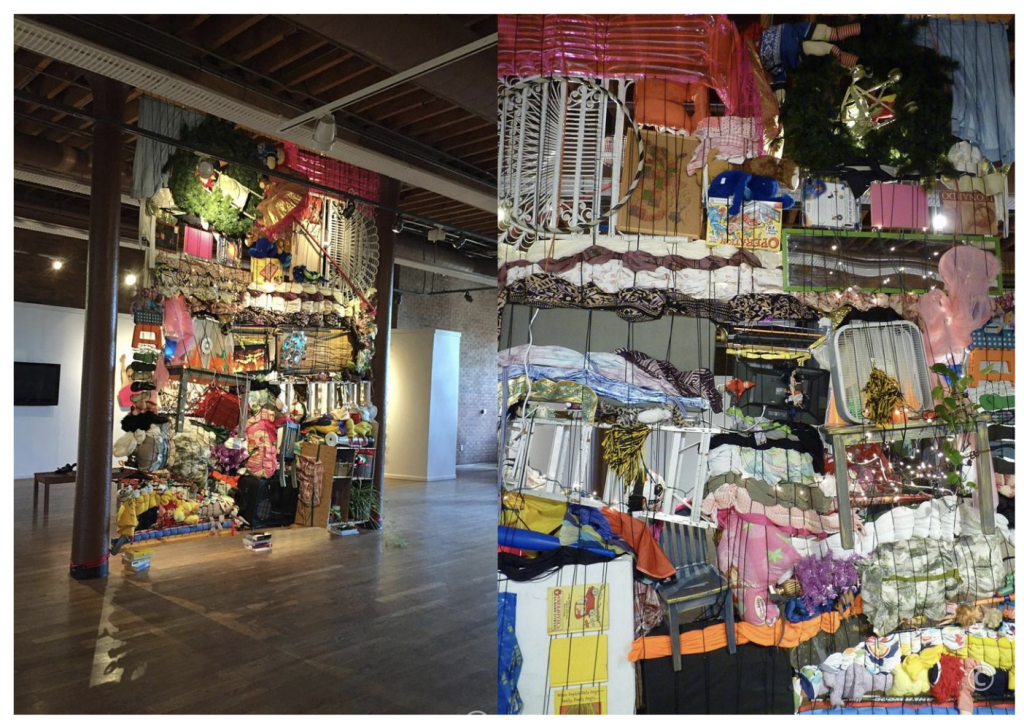

DK: In your works that are about stuff, like “Fabric of Life,” or the piece “Symphony of the Domestic II,” I keep thinking about the repetitive act of picking up and moving the stuff we surround ourselves with in the home, in our lives. The stuff you relocate to the gallery leaves a hole at home.

CK: That’s funny. At one point, a while ago, I had some work installed nearby, here at the Kennedy Museum of Art (Athens, OH). Chloé really likes split pea soup, so I went to find a mason jar of split peas on the shelf at home, and it was missing. I looked in all possible places, felt like I was losing my mind, until I realized I had included it in the installation at the gallery. So we have a joke that if we can’t find something, it’s probably in the gallery.

Using stuff from home does leave a vacancy, and it often feels good to have it out of the way. Sometimes it can be hard to find space for it when the show comes down, to fit it back into our lives. But I think that’s part of the work, the value of stuff in our lives, when we have someone we must care for outside of oneself. All the extra stuff that comes with caring for another human being. It’s the stuff, and the space provided for the other. All of this seems to come with having a child. With being a parent.

DK: Recognising the position or existence of the “other” seems to be near the heart of multiple ongoing conflicts in the world, it seems timely. What role do artists play in this moment?

CK: It’s been a very self-serving political climate for some time now. In light of recent changes, I’ve noticed more of a bend toward the political that might surface in my own work. I’ve not thought of being all that interested in politics until recently, which I think is related to our very tense political climate right now. You could include an “eyeroll” into the text here—and quote me on it!

For all the women artists in the world we’re still the minority, in terms of representation. Mothers especially, still are not a valid subject matter in the artworld. Legally, a hiring committee cannot ask if you have children, but of course it plays a part in negotiating for position, and compensation. I put it all out there, it’s not hidden. Statistically women who are mothers are paid less than other women, who are of course paid less than their male counterparts. The contradiction is that the role of mother is [recognized as] important, but don’t talk about it.

The expectation is to raise your children, discipline them, keep your house, care for them, but shut up about it. There are a growing number of artists internationally who are beginning to talk about it, to make it their subject matter.

Children have not been welcomed in the gallery for a long time. Even Judy Chicago welcomed dogs to her Womanhouse studios before children. I give tribute to the 60’s and 70’s because of the body work, the female forward work that they set out to do. But they had to push their family, and children aside, because they were competing with their male counterparts. I think of my work as in protest with that portion of their history.